HMGB1: cosa è e come può avere un ruolo nel Mesotelioma Pleurico Maligno

DEFINIZIONE

HMGB1 è una sigla che definisce High Mobility Group Box 1. Si tratta di una proteina che fa parte della famiglia delle high mobility group, ossia le proteine ad alta mobilità elettroforetica. (Con "mobilità elettroforetica" si intende una grandezza che definisce la capacità di una specie chimica di spostarsi quando sottoposta ad un campo elettrico e dipende solitamente da vari parametri, come per esempio, la carica, la dimensione, le caratteristiche conformazionali, la tensione applicata al campo e la concentrazione del mezzo elettroforetico).

Questa proteina viene definita anche anfoterina o HMG1 ed è una proteina non istonica strutturale della cromatina.

L'HMGB1, inoltre, viene classificata all'interno della sottofamiglia di quelle proteine contenenti un dominio coinvolto nel legame con il DNA: l' HMG-box.

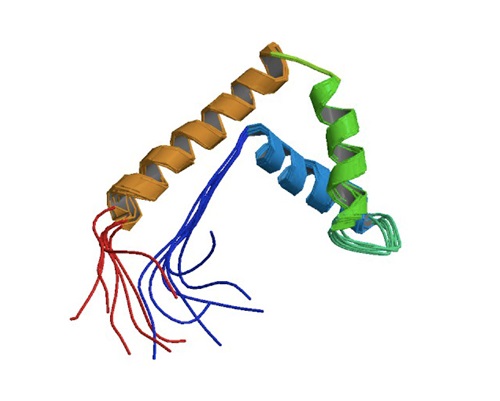

Di seguito viene riportata un'immagine tridimensionale della struttura di tale proteina.

(da PDB: Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1 aab)

Il gene HMGB1 è localizzato sul braccio lungo del cromosoma 13 13q12.

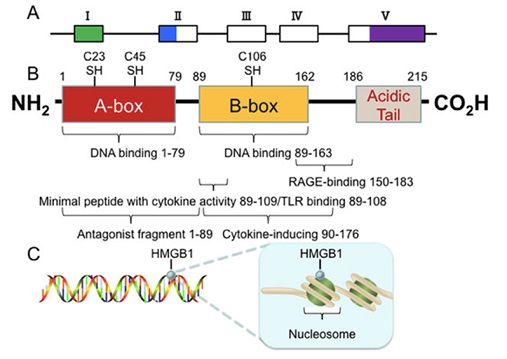

Nella figura sottostante, vengono rappresentati i 5 esoni del gene dell'HMGB1 sotto forma di piccoli parallelepipedi (vuoto per regioni tradotte e solido per regioni non tradotte).

Nella parte sottostante (B), sono rappresentati i 215 residui aminoacidici e tre domini che costituiscono la composizione: A box, B box e una coda acida C-terminal. Ci sono tre residui di cisteina nelle posizioni 23, 45 e 106, che regolano la funzione HMGB1 in risposta allo stress ossidativo.

Nella parte C della figura, si trova la rappresentazione dell'HMGB1 che è liberamente e transitoriamente associata ai nucleosomi. L'HMGB1 è importante per la segregazione spaziale e l'omeostasi nucleare.

(da He SJ, et al. Oncotarget. 2017)

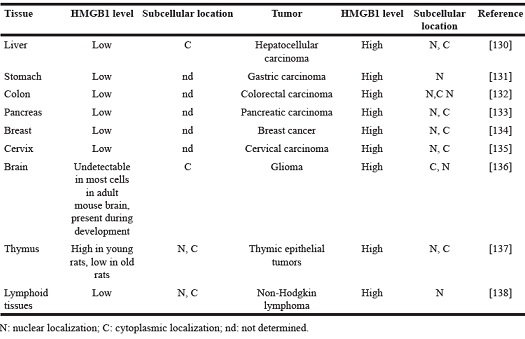

Generalmente, l'HMGB1 è espressa ubiquitariamente (solo 10 volte meno rispetto agli istoni principali). Tuttavia, l'espressione di HMGB1 e la localizzazione subcellulare variano a seconda dei tipi di cellule e dei tessuti e sono regolate dagli stimoli ambientali circostanti.

(da He SJ, et al. Oncotarget. 2017)

FUNZIONI PRINCIPALI

L'HMGB1 si trova in grandi quantità all'interno del nucleo di tutte le cellule eucariote ed ha come ruolo principale quello di rimodellare la cromatina.

Inoltre, è stato recentemente scoperto che tale proteina è un mediatore importante nel processo infiammatorio, soprattutto nel caso di necrosi cellulare. Pertanto, l'HMGB gioca un ruolo importante nell’innesco dell’infiammazione, ma sembrerebbe coinvolta anche nelle risposte innate ed adattative e nella riparazione del danno tissutale.

Le cellule sottoposte a stress secernono questa proteina. In particolare, HMGB1 passa dal nucleo al citoplasma e poi viene secreta attraverso lisosomi e direttamente nello spazio extracellulare.

(da Bianchi ME, et al. Immunol Rev. 2017)

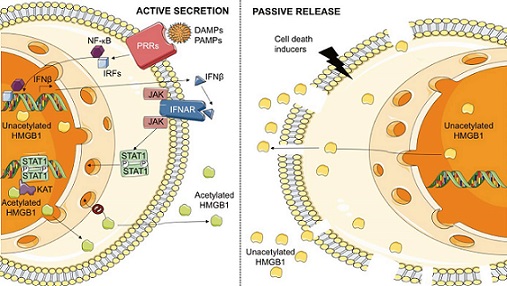

Come mostrato nella figura, l’HMGB1 è una proteina che può essere passivamente rilasciata dalle cellule morte, come mostrato a destra. In altri casi, invece, viene secrete attivamente come conseguenza di un stress cellulare, come mostrato a sinistra.

In condizioni normali, tale proteina è localizzata nel nucleo in una forma ridotta e non acetilata. In seguito a danno tissutale, tale proteina non modificata viene rilasciata dalle cellule morte e successivamente convertita nella forma disulfide-HMGB1 tramite una ossidazione spontanea, oppure attraverso le specie reattive dell’ossigeno (ROS) che vengono prodotte in modo abbondante dalle cellule infiammatorie.

Anche i leucociti possono secernere HMGB1: tale proteina viene prima di tutto spostata nel citoplasma e successivamente viene acetilata o fosforilata e dopo tali trasformazioni passa nello spazio extracellulare. Questo avviene molto spesso dopo essere stata caricata in lisosomi secretori che si trovano nei leucociti o attraverso un meccanismo poco conosciuto in cellule non ematopoietiche.

L’HMGB1 secreta può essere distinta da quella rilasciata passivamente (in giallo), a causa dello stato acetilato, che viene evidenziato in verde nella figura. Inoltre, la forma secreta viene ossidata.

Lo schema a sinistra rappresenta la via della secrezione di HMGB1 indotta da LPS e dagli interferoni in seguito ad un’infezione batterica o virale.

Le cellule immunitarie vengono reclutate nel sito in cui vi sia un danno tissutale e successivamente, quando si trovano in tale sede, vengono attivate.

La proteina HMGB1 supporta la riparazione tissutale e coordina l’attivazione dei macrofagi nel fenotipo utile per tale riparazione, attiva e incrementa la proliferazione delle cellule staminali e la neoangiogenesi. Purtroppo, allo stesso modo, tale proteina contribuisce alla riparazione tissutale di tutte le cellule danneggiate e tra queste vi sono anche quelle tumorali.

(da Bianchi ME, et al. Immunol Rev. 2017)

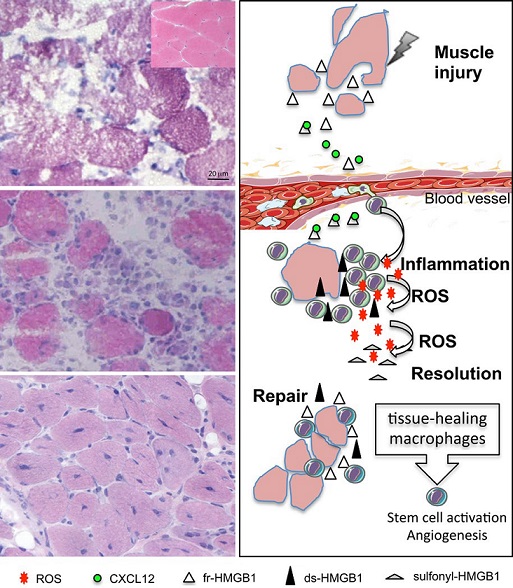

La figura rappresenta il ruolo dell'HMGB nella riparazione tissutale.

Come illustrato, tale proteina ha un'attività importante durante il danno muscolare.

Infatti, l'HMGB1 viene rilasciata dalle cellule muscolari che sono state danneggiate o sono in uno stato necrotico. Inoltre, questa proteina è in grado, in queste condizioni, di promuovere il reclutamento delle cellule del sistema immunitario come i leucociti, attraverso la formazione di eterocomplessi con CXCL12. Con l'arrivo dei leucociti a livello della sede di danno tissutale, si verifica uno stato di infiammazione. Pertanto, l'HMGB1 viene ossidata a disulfide attraverso i radicali liberi dell'ossigeno, che si formano in seguito all'infiltrazione dei leucociti. Inoltre, la HMGB1 attiva i leucociti a promuovere il rilascio di una serie di citochine e chemochine proinfiammatorie, ma perde la sua capacità di formare eterocoplessi con CXCL12.

Dopo la risoluzione dello stato infiammatorio, i macrofagi caratterizzati dal fenotipo utile al riparo tissutali rilasciano HMGB1, che può attivare le cellule staminali e promuovere l'angiogenesi, oltre che coordinare il riparo del danno muscolare.

HMGB1 E CANCRO

La proteina HMGB1 sembrerebbe avere un ruolo importante nella progressione del cancro.

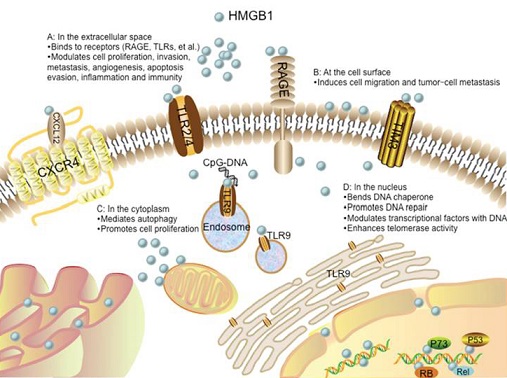

Nella figura sottostante, viene riassunto schematicamente come l'HMGB1 possa interagire a livello biologico per promuovere la cancerogenesi.

Nello spazio extracellulare, come mostrato nella parte A, i segnali di tale proteina sono promossi attraverso recettori quali RAGE, TLRs, TIM3, and CXCR4. Questa attivazione recettoriale porta alla proliferazione cellulare, all'incremento del processo di invasione e di angiogenesi, alla metastatizzazione, alla capacità di evitare l'apoptosi, all'aumento dell'infiammazione e dell'attivazione immunitaria. L'interazione tra HMGB1 e CXCR4 è dipendente da CXCL12. Il TLR9 è inizialmente localizzato a livello del reticolo endoplasmatico (ER) e successivamente ridistribuito agli endosomi sotto la stimolazione di CpG-DNA attraverso una via dipendente da HMGB1.

Nella parte B, HMGB1 è presente sulla superficie cellulare e promuove la migrazione delle cellule neoplastiche e la metastatizzazione tumorale.

Nel citoplasma, come mostrato nella parte C della figura, l'HMGB1 regola l'autofagia e promuove la proliferazione cellulare.

Nella parte D, invece, è rappresentata tale proteina a livello del nucleo, dove agisce come una chaperone e partecipa alla riparazione del DNA ed alla trascrizione. L'HMGB1 può interagire con fattori di trascrizione, quali p53, p73 e RB ed incrementare la loro attivazione. La HMGB1 nucleare incrementa l'attività delle telomerasi e modula l'omeostasi dei telomeri.

(da He SJ, et al. Oncotarget. 2017)

HMGB1 E MESOTELIOMA PLEURICO MALIGNO

La proteina HMGB1 è profondamente implicata nella biologia tumorale.

L’HMGB1 sembrerebbe essere correlata con il mesotelioma. In questa neoplasia, l’asbesto causa infiammazione del mesotelio, ma le vie biomolecolari che stanno alla base di tale processo infiammatorio- neoplastico non sono completamente conosciuti.

Tuttavia, recentemente è stato scoperto che l’asbesto induce morte delle cellule mesoteliali per necrosi, con conseguente rilascio di HMGB1 nello spazio extracellulare e richiamo di cellule infiammatorie.

La persistenza delle fibre di asbesto è una delle cause principali del perpetuarsi dello stato infiammatorio pleurico e spesso polmonare dei soggetti che sono stati esposti a tale cancerogeno e che poi sviluppano MPM. Sono stati dimostrati alti livelli di HMGB1nel sangue sia di soggetti esposti ad amianto che di malati di MPM, questo a riprova del fatto che tale proteina sembrerebbe davvero implicata in questi processi di infiammazione e carcinogenesi. Anche in questo caso non è perfettamente chiaro come l’infiammazione persistente possa tramutarsi in stimolo alla carcinogenesi, ma alcuni studi suggeriscono il ruolo dei macrofagi nella sopravvivenza cellulare.

Una prova di tale ipotesi, sta nel fatto che i macrofagi sono stati riscontrati in abbondanza nel tessuto neoplastico.

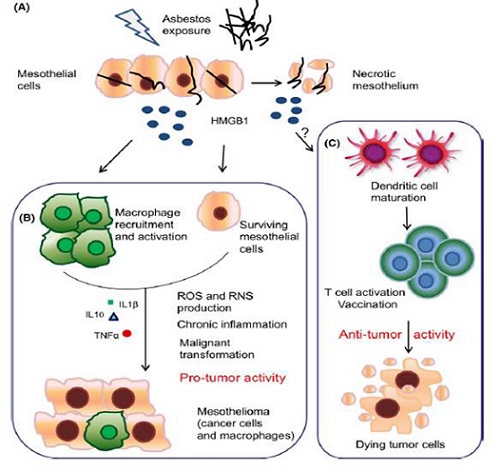

Di seguito viene riportata una rappresentazione schematica delle attività della HMGB1 protumorali o antitumorali.

Nella parte A della figura le cellule mesoteliali subiscono un danno da parte dell’esposizione all’asbesto e sono portate a mettere in atto la morte programmata necrotica con il conseguente rilascio di HMGB1.

La parte B della figura rappresenta, invece, le attività protumorali della proteina HMGB1. l’HMGB1 lega il TLR4 e genera uno stato di infiammazione cronica che porta con il cronicizzarsi di tale situazione alla trasformazione maligna. I macrofagi sono presenti nel tessuto mesoteliale e l’HMGB1 è secreta costitutivamente dalle cellule di mesotelioma.

Nella parte C della figura sono, invece, rappresentate le caratteristiche antitumorali di tale proteina. Il punto di domanda riportato nell'immagine denota il fatto che non siano mai stati completamente investigati i meccanismi che coinvolgono l’HMGB1 e la patogenesi del mesotelioma.

In ogni caso, è stato ampiamente documentato il coinvolgimento di tale proteina nell'attività anticancro contro diversi tumori. L’HMGB1 è secreta dalle cellule e probabilmente coinvolta nei meccanismi che portano alla risposta delle cellule B e T portato ad una memoria immunologica.

(da Bianchi ME, et al. Immunol Rev. 2017)

CONCLUSIONI

Pertanto lo studio e l’approfondimento di tale proteina potranno contribuire ad una maggiore comprensione della patogenesi del cancro.

In particolare, molti autori stanno cercando di definire il reale ruolo dell'HMGB1 nel mesotelioma pleurico maligno per definire meglio la cancerogenesi di tale malattia.

Le prospettive future mirano anche a disegnare eventuali approcci terapeutici che possano coinvolgere tale proteina o le vie da essa attivate.

REFERENZE

1. Janeway CA Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197‐216.

2. Matzinger P. The danger model: A renewed sense of self. Science. 2002;296:301‐305.

3. Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418:191‐ 195.

4. Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, et al. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 1999;285:248‐251.

5. Falciola L, Spada F, Calogero S, et al. High mobility group 1 (HMG1) protein is not stably associated with the chromosomes of somatic cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:19‐26.

6. Rovere-Querini P, Capobianco A, Scaffidi P, et al. HMGB1 is an endogenous immune adjuvant released by necrotic cells. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:825‐ 830.

7. Messmer D, Yang H, Telusma G, et al. High mobility group box protein 1: An endogenous signal for dendritic cell maturation and Th1 polarization J Immunol. 2004;173:307‐313.

8. Dumitriu IE, Baruah P, Valentinis B, et al. Release of High Mobility Group Box 1 by dendritic cells controls T cell activation via the receptor for

advanced glycation end products. J Immunol. 2005;174:7506‐7515.

9. Dumitriu IE, Bianchi ME, Bacci M, Manfredi AA, Rovere-Querini P. The secretion of HMGB1 is required for the migration of maturing dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:84‐91.

10. Chen GY, Tang J, Zheng P, Liu Y. CD24 and Siglec-10 selectively repress tissue damage-induced immune responses. Science. 2009;323:1722‐ 1725.

11. Chiba S, Baghdadi M, Akiba H, et al. Tumor-infiltrating DCs suppress nucleic acid-mediated innate immune responses through interactions between the receptor TIM-3 and the alarmin HMGB1. Nat Immunol. 2012;3:832‐842.

12. Gardella S, Andrei C, Ferrera D, et al. The nuclear protein HMGB1 is secreted by monocytes via a non- classical, vesicle-mediated secretory pathway. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:995‐1001.

13. Bonaldi T, Talamo F, Scaffidi P, et al. Monocytic cells hyperacetylate chromatin protein HMGB1 to redirect it towards secretion. EMBO J.

2003;22:5551‐5560.

14. Oh YJ, Youn JH, Ji Y, et al. HMGB1 is phosphorylated by classical protein kinase C and is secreted by a calcium-dependent mechanism. J

Immunol. 2009;182:5800‐5809.

15. Tsung A, Klune JR, Zhang X, et al. HMGB1 release induced by liver ischemia involves Toll-like receptor 4 dependent reactive oxygen species production and calcium-mediated signaling. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2913‐ 2923.

16. Lu B, Antoine DK, Kwan K, et al. JAK/STAT1 signaling promotes HMGB1 hyperacetylation and nuclear translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:3068‐3073.

17. Hoppe G, Talcott KE, Bhattacharya SK, Crabb JW, Sears JE. Molecular basis for the redox control of nuclear transport of the structural chromatin protein Hmgb1. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:3526‐3538.

18. Venereau E, Casalgrandi M, Schiraldi M, et al. Mutually exclusive redox forms of HMGB1 promote cell recruitment or proinflammatory cytokine release. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1519‐1528.

19. Schiraldi M, Raucci A, Munoz LM, et al. HMGB1 promotes recruitment of inflammatory cells to damaged tissues by forming a complex with CXCL12 and signaling via CXCR4. J Exp Med. 2012;209:551‐563.

20. Pawig L, Klasen C, Weber C, Bernhagen J, Noels H. Diversity and inter-connections in the CXCR4 chemokine receptor/ligand family: Molecular perspectives. Front Immunol. 2015;6:429.

21. Collins PJ, McCully ML, Martinez-Munoz L, et al. Epithelial chemokine CXCL14 synergizes with CXCL12 via allosteric modulation of CXCR4. FASEB J. 2017;31:3084‐3097.

22. Yang H, Wang H, Ju Z, et al. MD-2 is required for disulfide HMGB1- dependent TLR4 signaling. J Exp Med. 2015;212:5‐14.

23. Yang H, Hreggvidsdottir HS, Palmblad K, et al. A critical cysteine is required for HMGB1 binding to Toll- like receptor 4 and activation of macrophage cytokine release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11942‐11947.

24. Abraham E, Arcaroli J, Carmody A, Wang H, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 as a mediator of acute lung inflammation. J Immunol. 2000;165:2950‐2954.

25. Tsung A, Sahai R, Tanaka H, et al. The nuclear factor HMGB1 mediates hepatic injury after murine liver ischemia-reperfusion. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1135‐1143.

26. Muhammad S, Barakat W, Stoyanov S, et al. The HMGB1 receptor RAGE mediates ischemic brain damage. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12023‐12031.

27. Weng H, Deng Y, Xie Y, Liu H, Gong F. Expression and significance of HMGB1, TLR4 and NF-kappaB p65 in human epidermal tumors. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:311.

28. Maroso M, Balosso S, Ravizza T, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 and high mobility group box-1 are involved in ictogenesis and can be targeted to reduce seizures. Nat Med. 2010;16:413‐ 419.

29. Agalave NM, Larsson M, Abdelmoaty S, et al. Spinal HMGB1 induces TLR4-mediated

long-lasting hypersensitivity and glial activation and regulates pain- like behavior in experimental arthritis. Pain. 2014;155:1802‐1813.

30. Ma F, Kouzoukas DE, Meyer- Siegler KL, Westlund KN, Hunt DE, Vera PL. Disulfide high mobility group box- 1 causes bladder pain through bladder Toll-like receptor 4. BMC Physiol. 2017;17:6.

31. Tian J, Avalos AM, Mao SY, et al. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:487‐496.

32. Ivanov S, Dragoi AM, Wang X, et al. A novel role for HMGB1 in TLR9- mediated inflammatory responses to CpG-DNA. Blood. 2007;110:1970‐1981.

33. Urbonaviciute V, Furnrohr BG, Meister S, et al. Induction of inflammatory and immune responses by HMGB1-nucleosome complexes: Implications for the pathogenesis of SLE. J Exp Med. 2008;295:3007‐3018.

34. Parkkinen J, Raulo E, Merenmies J, et al. Amphoterin, the 30 kDa protein in a family of HMG1-type polypeptides. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19726‐19738.

35. Sessa L, Gatti E, Zeni F, et al. The receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) is only present in mammals, and belongs to a family of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs). PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86903.

36. Fritz G. RAGE: A single receptor fits multiple ligands. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:625‐632.

37. Raucci A, Cugusi S, Antonelli A, et al. A soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is produced by proteolytic cleavage of the membrane- bound form by the sheddase a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10). FASEB J. 2008;22:3716‐3727.

38. Braley A, Kwak T, Jules J, Harja E, Landgraf R, Hudson BI. Regulation of receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) ectodomain shedding and its role in cell function. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:12057‐12073.

39. Kokkola R, Andersson A, Mullins G, et al. RAGE is the major receptor for the proinflammatory activity of HMGB1 in rodent macrophages. Scand J Immunol. 2005;61:1‐9.

40. Fiuza C, Bustin M, Talwar S, et al. Inflammatory promoting activity of HMGB1 on human microvascular endothelial cells. Blood. 2002;27:2652‐2660.

41. Kew RR, Penzo M, Habiel DM, Marcu KB. The IKKalpha-dependent NF- kappaB p52/RelB noncanonical pathway is essential to sustain a CXCL12 autocrine loop in cells migrating in response to HMGB1. J Immunol. 2012;188:2380‐2386.

42. Vogel S, Bodenstein R, Chen Q, et al. Platelet-derived HMGB1 is a critical mediator of thrombosis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4638‐4654.

43. Stark K, Philippi V, Stockhausen S, et al. Disulfide HMGB1 derived from platelets coordinates venous thrombosis in mice. Blood. 2016;128:2435‐2449.

44. Mitola S, Belleri M, Urbinati C, et al. Cutting edge: Extracellular high mobility group box-1 protein is a proangiogenic cytokine. J Immunol. 2006;176:12‐15.

45. Venereau E, Schiraldi M, Uguccioni M, Bianchi ME. HMGB1 and leukocyte migration during trauma and sterile inflammation. Mol Immunol. 2013;55:76‐82.

46. Venereau E, Ceriotti C, Bianchi ME. DAMPs from cell death to new life. Front Immunol. 2015;6:422.

47. Dormoy-Raclet V, Cammas A, Celona B, et al. HuR and miR-1192 regulate myogenesis by modulating the translation of HMGB1 mRNA. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2388.

48. van Beijnum JR, Dings RP, van der Linden E, et al. Gene expression of tumor angiogenesis dissected: Specific targeting of colon cancer angiogenic vasculature. Blood. 2006;108:2339‐2348.

49. Campana L, Santarella F, Esposito A, et al. Leukocyte HMGB1 is required for vessel remodeling in regenerating muscles. J Immunol. 2014;192:5257‐5264.

50. Palumbo R, Sampaolesi M, De Marchis F, et al. Extracellular HMGB1, a signal of tissue damage, induces mesoangioblast migration and proliferation. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:441‐449.

51. Limana F, Germani A, Zacheo A, et al. Exogenous high-mobility group box 1 protein induces myocardial regeneration after infarction via enhanced cardiac C-kit+ cell proliferation and differentiation. Circ Res. 2005;97:e73‐83.

52. Meng E, Guo Z, Wang H, et al. High mobility group box 1 protein inhibits the proliferation of human mesenchymal stem cells and promotes their migration and differentiation along osteoblastic pathway. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:805‐813.

53. Lotfi R, Eisenbacher J, Solgi G, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells respond to native but not oxidized damage associated molecular pattern molecules from necrotic (tumor) material. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2021‐ 2028.

54. Tamai K, Yamazaki T, Chino T, et al. PDGFR{alpha}-positive cells in bone marrow are mobilized by high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) to regenerate injured epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6609‐6614.

55. Chavakis E, Hain A, Vinci M, et al. High-mobility group box 1 activates integrin-dependent

56. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646‐674.

57. Carbone M, Yang H. Mesothelioma: Recent highlights. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:238.

58. Yang H, Rivera Z, Jube S, et al. Programmed necrosis induced by asbestos in human mesothelial cells causes high-mobility group box 1 protein release and resultant inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:12611‐12616.

59. Napolitano A, Antoine DJ, Pellegrini L, et al. HMGB1 and its hyper-acetylated isoform are sensitive and specific serum biomarkers to detect asbestos exposure and to identify mesothelioma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3087‐3096.

60. Cornelissen R, Lievense LA, Maat AP, et al. Ratio of intratumoral macrophage phenotypes is a prognostic factor in epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e106742.

61. Jube S, Rivera ZS, Bianchi ME, et al. Cancer cell secretion of the DAMP protein HMGB1 supports progression in malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3290‐3301.

62. Yang H, Pellegrini L, Napolitano A, et al. Aspirin delays mesothelioma growth by inhibiting HMGB1-mediated tumor progression. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1786.

63. Pellegrini L, Xue J, Larson D, et al. HMGB1 targeting by ethyl pyruvate suppresses malignant phenotype of human mesothelioma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:22649‐22661.

64. Cottone L, Capobianco A, Gualteroni C, et al. Leukocytes recruited by tumor-derived HMGB1 sustain peritoneal carcinomatosis. Oncoimmunol. 2016;5:e1122860.

65. Mittal D, Saccheri F, Venereau E, Pusterla T, Bianchi ME, Rescigno M. TLR4-mediated skin carcinogenesis is dependent on immune and radioresistant cells. EMBO J. 2010;29:2242‐2252.

66. Bald T, Quast T, Landsberg J, et al. Ultraviolet-radiation- induced inflammation promotes angiotropism and metastasis in melanoma. Nature. 2014;507:109‐113.

67. Guo ZS, Liu Z, Bartlett DL, Tang D, Lotze MT. Life after death: Targeting high mobility group box 1 in emergent cancer therapies. Am J Cancer Res. 2013;3:1‐20.

68. Cottone L, Capobianco A, Gualteroni C, et al. 5-Fluorouracil causes leukocytes attraction in the peritoneal cavity by activating autophagy and HMGB1 release in colon carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1381‐1389.

69. Galluzzi L, Buque A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:97‐ 111.

70. Demaria S, Ng B, Devitt ML, et al. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:862‐ 870.

71. Casares N, Pequignot MO, Tesniere A, et al. Caspase-dependent immunogenicity of doxorubicin-induced tumor cell death. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1691‐1701.

72. Krysko DV, Garg AD, Kaczmarek A, Krysko O, Agostinis P, Vandenabeele P. Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:860‐875.

73. Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med. 2007;13:1050‐ 1059.

74. Ladoire S, Penault-Llorca F, Senovilla L, et al. Combined evaluation of LC3B puncta and HMGB1 expression predicts residual risk of relapse after adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Autophagy. 2015;11:1878‐1890.

75. Yamazaki T, Hannani D, Poirier- Colame V, et al. Defective immunogenic cell death of HMGB1-deficient tumors: Compensatory therapy with TLR4 agonists. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:69‐78.

76. Sistigu A, Yamazaki T, Vacchelli E, et al. Cancer cell- autonomous contribution of type I interferon signaling to the efficacy of chemotherapy. Nat Med. 2014;20:1301‐1309.

77. Garg AD, Krysko DV, Verfaillie T, et al. A novel pathway combining calreticulin exposure and ATP secretion in immunogenic cancer cell death. EMBO J. 2012;31:1062‐1079.

78. Trisciuoglio L, Bianchi ME. Several nuclear events during apoptosis depend on caspase-3 activation but do not constitute a common pathway. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6234.

79. Kazama H, Ricci JE, Herndon JM, Hoppe G, Green DR, Ferguson TA. Induction of immunological tolerance by apoptotic cells requires caspase- dependent oxidation of high-mobility group box-1 protein. Immunity. 2008;29:21‐32.

80. Goodwin GH, Sanders C, Johns EW. A new group of chromatin- associated proteins with a high content of acidic and basic amino acids. Eur J Biochem. 1973;38:14‐19.

81. Agresti A, Bianchi ME. HMGB proteins and gene expression. Curr Op Genet Develop. 2003;13:170‐178.

82. Sessa L, Bianchi ME. The evolution of High Mobility Group Box (HMGB) chromatin proteins in multicellular animals. Gene. 2007;387:133‐140.

83. Giavara S, Kosmidou E, Hande MP, et al. Yeast Nhp6A/B and mammalian Hmgb1 facilitate the maintenance of genome stability. Curr Biol. 2005;15:68‐72.

84. Celona B, Weiner A, Di Felice F, et al. Substantial histone reduction modulates genomewide nucleosomal occupancy and global transcriptional output. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001086.

85. Choi HW, Manohar M, Manosalva P, Tian M, Moreau M, Klessig DF. Activation of plant innate immunity by extracellular high mobility group box 3 and its inhibition by salicylic acid. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005518.

86. Li J, Zhang Y, Xiang Z, Xiao S, Yu F, Yu Z. High mobility group box 1 can enhance NF-κB activation and act as a pro-inflammatory molecule in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013;35:63‐70.

87. Venereau E, De Leo F, Mezzapelle R, Careccia G, Musco G, Bianchi ME. HMGB1 as biomarker and drug target. Pharmacol Res. 2016;111:534‐544.

88. Bianchi ME, Manfredi AA. How macrophages ring the inflammation alarm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:2866‐2867. homing of endothelial progenitor cells. Circ Res. 2007;100:204‐212.

89. He SJ, Cheng J, Feng X, Yu Y, Tian L, Huang Q. The dual role and therapeutic potential of high-mobility group box 1 in cancer. Oncotarget. 2017 May 16;8(38):64534-64550. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17885. eCollection 2017 Sep 8.

90. Ferrari, S., Finelli, P., Rocchi, M., Bianchi, M. E. The active gene that encodes human high mobility group 1 protein (HMG1) contains introns and maps to chromosome 13. Genomics 35: 367-371, 1996. PMID 8661151

91. Bianchi ME, Crippa MP, Manfredi AA, Mezzapelle R, Rovere Querini P, Venereau E1. High-mobility group box 1 protein orchestrates responses to tissue damage via inflammation, innate and adaptive immunity, and tissue repair. Immunol Rev. 2017 Nov;280(1):74-82. doi: 10.1111/imr.12601.